Internet Policy in China

A Field Study of Internet Cafés

INTRODUCTION

More than forty years ago, in writing about a new mass medium, Marshall McLuhan predicted the coming of a “Global Village,” where he imagined all people would coexist in a state of active interplay, because “electric media in-stantly and constantly create a total field of interacting events in which all men participate.” With the advent of digital technologies now worldwide, we hear that an “Information Age” has arrived and that the Internet will help us win the final victory for democracy. Indeed, Internet technology has freed us from geographical and time constraints, provided us with potential public spheres for civic engagement, and lessened control and manipulation of knowledge and information by government bureaucracies.

Yet technological revolutions often unfold along unexpected trajectories. The advances in electronics and optics over the past decades also appear to have reinforced existing power centers in capitalist countries by relentlessly concentrating ownership and in modernizing countries by justifying more bureaucracies, regulations, and state-owned monopolies. Nine years into the twenty-first century, we seem to be moving toward the “global village” slowly and unsurely, and both modernized and modernizing countries are facing multiple choices. This work studies these choices in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) through a multi-layered examination of the Internet café phenomenon in the rapidly changing country.

Since 1978 when Deng Xiaoping, the principal leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) after the Mao Zedong era (1949-1976), launched key economic reforms, changes have taken place in almost every aspect of people’s lives. At the same time, however, there has been a basic continuity. The CCP leadership has kept its essential features, though it has steered the nation’s development in a new, quasi-capitalist, direction. Claiming to be the representative of the people, the Party-led government still dominates all political, social, and cultural spheres as “public” spheres under its ownership and supervision.

Especially notable has been the phenomenal growth and unlimited power of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs), both competing and collaborating with private corporations from the West. Much like their Western counterparts, the Chinese SOEs have expanded their economic, political, and cultural role throughout the reform years from the late 1970s to the present. While Western private media conglomerates have spread their corporate culture all over the world, the SOEs have become mighty profit centers; they have also learned a great deal about amassing political power, which few have the authority to regulate or challenge. Armed with newly imported information and communication technologies (ICT), the SOEs have greatly strengthened the CCP leadership.

It seems every time capitalism thrives in China with its technological advances, it serves the state well by solving technological or economic problems, but offers not much to the common wealth or welfare of ordinary citizens. The capitalism sweeping throughout China since the 1980s appears to follow this pattern.

Using an analysis of technology as a departure point in the inquiry about techno-socio relationships in China, this book seeks to describe and explain the present, relatively successful coexistence and collaboration between Western capitalism and Communist statism in China at the time of the arrival of Internet technology.

The work combines a field study on the Chinese Internet café phenomenon with historical and critical analysis of Chinese statism, in order to investigate what roles Internet technology has played in Chinese society. What has the state achieved with the help of the Internet? Is the Internet a real threat to the Party-state? Does technology interact with society differently in the Chinese social, economic, legal, and political spheres from what prevails in Western nations?

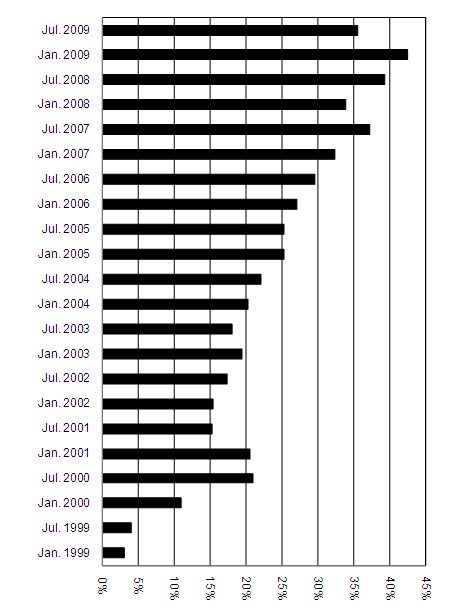

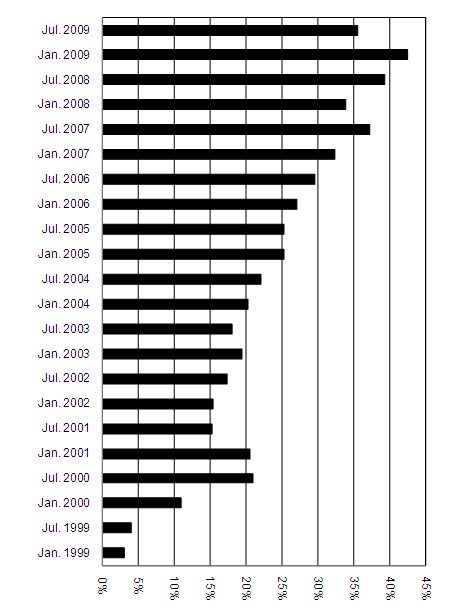

Chinese Netizens Accessing the Internet at Net Bars 1999-2009

A Field Study of Internet Cafés

INTRODUCTION

More than forty years ago, in writing about a new mass medium, Marshall McLuhan predicted the coming of a “Global Village,” where he imagined all people would coexist in a state of active interplay, because “electric media in-stantly and constantly create a total field of interacting events in which all men participate.” With the advent of digital technologies now worldwide, we hear that an “Information Age” has arrived and that the Internet will help us win the final victory for democracy. Indeed, Internet technology has freed us from geographical and time constraints, provided us with potential public spheres for civic engagement, and lessened control and manipulation of knowledge and information by government bureaucracies.

Yet technological revolutions often unfold along unexpected trajectories. The advances in electronics and optics over the past decades also appear to have reinforced existing power centers in capitalist countries by relentlessly concentrating ownership and in modernizing countries by justifying more bureaucracies, regulations, and state-owned monopolies. Nine years into the twenty-first century, we seem to be moving toward the “global village” slowly and unsurely, and both modernized and modernizing countries are facing multiple choices. This work studies these choices in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) through a multi-layered examination of the Internet café phenomenon in the rapidly changing country.

Since 1978 when Deng Xiaoping, the principal leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) after the Mao Zedong era (1949-1976), launched key economic reforms, changes have taken place in almost every aspect of people’s lives. At the same time, however, there has been a basic continuity. The CCP leadership has kept its essential features, though it has steered the nation’s development in a new, quasi-capitalist, direction. Claiming to be the representative of the people, the Party-led government still dominates all political, social, and cultural spheres as “public” spheres under its ownership and supervision.

Especially notable has been the phenomenal growth and unlimited power of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs), both competing and collaborating with private corporations from the West. Much like their Western counterparts, the Chinese SOEs have expanded their economic, political, and cultural role throughout the reform years from the late 1970s to the present. While Western private media conglomerates have spread their corporate culture all over the world, the SOEs have become mighty profit centers; they have also learned a great deal about amassing political power, which few have the authority to regulate or challenge. Armed with newly imported information and communication technologies (ICT), the SOEs have greatly strengthened the CCP leadership.

It seems every time capitalism thrives in China with its technological advances, it serves the state well by solving technological or economic problems, but offers not much to the common wealth or welfare of ordinary citizens. The capitalism sweeping throughout China since the 1980s appears to follow this pattern.

Using an analysis of technology as a departure point in the inquiry about techno-socio relationships in China, this book seeks to describe and explain the present, relatively successful coexistence and collaboration between Western capitalism and Communist statism in China at the time of the arrival of Internet technology.

The work combines a field study on the Chinese Internet café phenomenon with historical and critical analysis of Chinese statism, in order to investigate what roles Internet technology has played in Chinese society. What has the state achieved with the help of the Internet? Is the Internet a real threat to the Party-state? Does technology interact with society differently in the Chinese social, economic, legal, and political spheres from what prevails in Western nations?